[ad_1]

After a brilliant design career in Los Angeles, Don Weller left the pavement and palm trees for the artistic inspiration of the saddle and the Western life of his youth.

Growing up in Pullman, Washington, during World War II, Western artist Don Weller lived an idyllic childhood: hot dusty summers riding horses, YMCA camp, fishing Idaho lakes, and cold, snowy winters filled with perilous sledding excursions. Buffalo, Indians, cattle, and cowboys were long gone from the picturesque college town, but that did not thwart the youngster’s relentless quest to learn all about them. Weller and his horse Sandy would roam the rolling hills of the Palouse region around his home in pursuit of cowboys, but to no avail. When he wasn’t searching for them, he was drawing, painting, reading about, and studying them in movies and book illustrations, constantly fueling his imaginative pursuit of the bold, romanticized Western lifestyle.

“My problem when I was a little kid was that I had a horse and I had the fantasy that I was going to be a cowboy, but there weren’t cows around Pullman,” Weller says from the Utah ranch he shares with his wife, Cha Cha. “There were some farms to the south around the Snake River in Idaho — that was cattle country, and you’d get cowboys there. So, there were cowboys around, but not right by where I was. I found out where and when the rodeo team practiced, and I’d ride my horse out to the country and look across the fence to watch them and see what they were doing. It wasn’t long before they were teaching me to rope calves. They weren’t real cowboys, they were students, but they had come from ranches, they knew how to rope calves, and that was as close to cowboys as I could get. That was how I got started roping calves and learned a lot of cowboy behavior.”

He roped calves in high school and competed as a member of his college rodeo club.

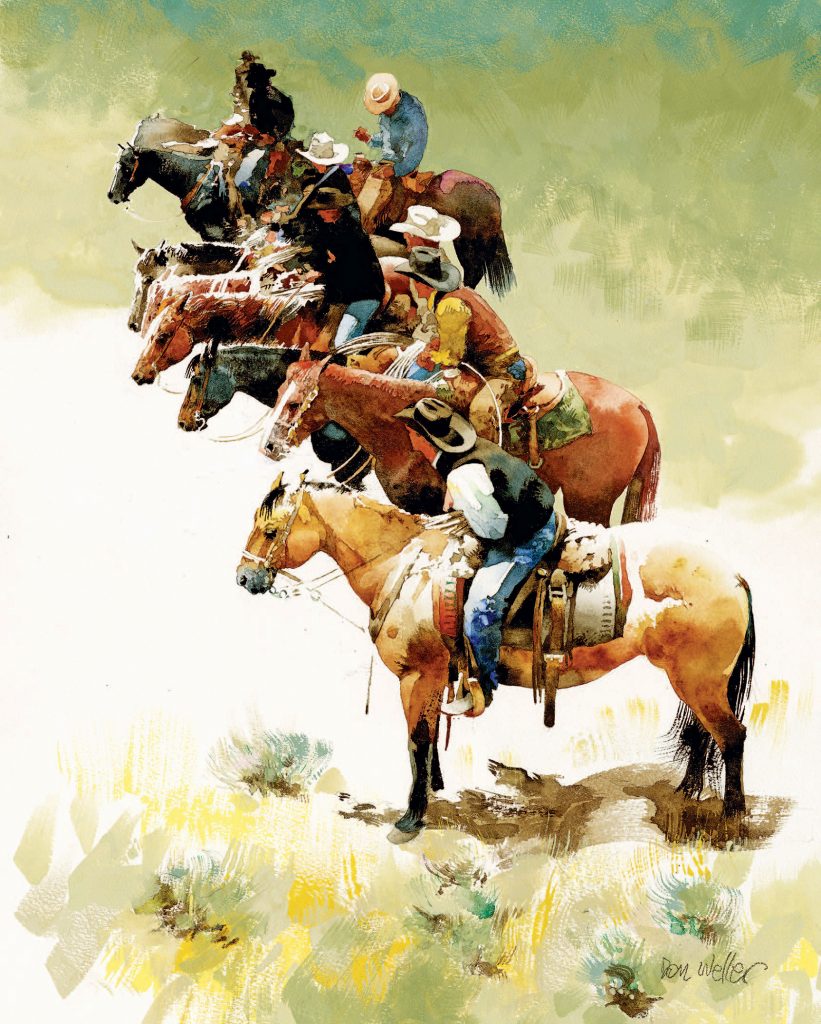

Eight Saddles Bein’ Sat

“When I was in college on the rodeo team and the other guys would go home to their ranches for Christmas and spring break, I’d go with them and live with their families for a few weeks on the ranch. We’d rope calves every day during the break and then go back to school.” He ultimately determined he “wasn’t fast enough” to make a living roping calves, and, discovering that a career in veterinary medicine was going to take longer than he wanted to stay in school, Weller went to his fallback position: art. Fortunately, he had taken a lot of art electives but was trained in the modern and abstract expressionist style in vogue at the time — genres that did not encourage the painting of cowboys. After graduating from Washington State University with a degree in fine art in 1960, Weller sold his horses, put cowboying and painting the cowboy life on hold, and moved to Los Angeles. There, for the next 25 years, he enjoyed success and international renown as a graphic artist and illustrator. He did album covers; magazine covers for Time and TV Guide; illustrations for Sports Illustrated, Boys’ Life, Pro, Reader’s Digest, among others; posters for the Hollywood Bowl, the NFL, and the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics; art for three children’s books; and five stamps for the U.S. Postal Service.

After all those gigs, as well as stints teaching at UCLA and the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, his California chapter finally came to an end. Don and Cha Cha decided they had “seen enough palm trees and cement” and headed to Utah. There, nestled in the hills, under majestic mountains and expansive skies, his heart and attention returned to his first love: cowboys and horses.

“When we moved to Park City, I started doing some paintings just for fun and got them into art shows, and people started buying them,” Weller says. “At first, I was doing it as a hobby, but it was more fun than doing illustrations for clients. One of the early projects we got in Park City was to design the Park City magazine, which we did for 25 years after moving here. I did a lot of illustrations in there and hired the photography and used a lot of illustrations from my old pals in New York and L.A. It made the transition easier.”

A book for the National Cutting Horse Association in 1990 and a follow-up book, Pride in the Dust, in 1997, introduced him to a neighbor who trained cutting horses; the project took him to arenas and ranches in Texas, Arizona, California, and Montana. The West of his youth “came flooding back,” and Weller once again devoted himself to painting and riding.

“A lot of people my age would have the same story,” he says. “We watched Roy Rogers and Gene Autry on the Saturday morning movies and that probably was the beginning. The books that I read were Will James cowboy stories, illustrated by his pen-and-ink drawings. Later, when I got to Utah, I started showing horses and competing. A lot of the friends I have in cutting would tell you the same story: They watched cowboy movies when they were little kids. Then they had a period when they had their business and forgot all about their cowboy roots, and then when they got old enough — in their 40s and 50s — and were able to afford a hobby that is sometimes kind of expensive, they reverted back and started riding cutting horses.”

In 2016 a retrospective exhibit called Don Weller: Another Cowboy at Park City’s Kimball Art Center included 90 of Weller’s Western watercolors; the enthusiastic reception prompted him to gather his Western work and the stories behind them for a memoir. The collected stories and evocative art — 130 paintings as well as sketches and illustrations chronicling his career — unfold over the 200 memorable pages of Don Weller Tracks: A Visual Memoir. The recipient of the prestigious 2020 Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in the literature category, the book reveals the wit and charm of a good-natured, tough-skinned, soft-hearted cowboy in frequently comical, always insightful stories and evocative images that resonate with a strong sense of place and the powers of observation of an authentic Westerner.

Evening on the River

“I started out drawing and painting cowboys and had some complicated but interesting detours. And although the tracks led far afield, I’m still painting cowboys,” Weller writes in the foreword. “The progression of projects outside the normal realm of Western art, and what I learned from them, help give my paintings their uniqueness and personality. First, I emulated Charles Russell, Will James, and George Phippen; then I added a touch of impressionism from art history and a little expressionism from the 1960s; then I dabbled in illustration and design in Los Angeles; and here we are today. The paintings are my teachers, and I learn from each one. Painting is learning. Learning is evolving. I’m left with the notion that composition and value are the most important aspects of a good painting. And that subject and color get the glory.”

Don, Cha Cha, their border collie (Buster), two cats, and five bred-to-cut horses live outside of Park City, in rural Oakley, where, naturally, there’s a rodeo. Now in his 80s, Weller still rides and cuts cows in his own round pen just for fun and remains a Westerner through and through. And he’s still painting cowboys — for purchase, for pleasure, for posterity.

We look back on his life and career with some excerpts from Don Weller Tracks.

Young Cowboy

“When I wasn’t drawing cowboys, or examining them in the movies or in books, I spent my time broadcasting my need to have my own horse. I worked hard on both my mother and father, but I sensed weakness first in my mom. I tried an all-out assault. Finally, resistance collapsed, and my dad went along. I named the horse Smoky, after my favorite book, and rode him everywhere, looking for cowboys. Since we had to board him, I did not learn responsibility the way my mother and I had hoped. So, my dad designed a new house, and we moved onto 20 acres outside of town. Neither of my folks knew the first thing about horses. Smoky was plenty gentle, but he was big, and my mom soon realized that having him was more complicated than she had planned. Watching me zoom around, she felt it would be a good idea to get me a saddle and have me learn something about horses and their care. To this end, she found Clay Burnam, a horseman and veterinary medicine student at WSU. He was as close to a real cowboy as I’d found so far. Clay taught me a lot of horsemanship and helped me find a new horse, Sandy, a palomino colt, who had not yet been handled. He had a kind eye, quiet demeanor, reasonably good conformation, and no registration papers. He was, what was called in those days, quarter horse type. He was 2 years old. I taught him, and he taught me. We explored everywhere a horse could go, up and down the Palouse River, all the dirt and gravel roads, around wheat fields. Everywhere. We did spins and sliding stops, ran barrels and poles, jumped logs. He was always eager but never bucked.”

College Rodeo Days

“I went to college simply because I had no other ideas. … First enroll, then rush to join the rodeo club. …

“At our house, we had a bucking barrel. It was an old oil drum with four ropes attached. You can’t find them anymore, but in the rural West in the ’50s, they were as common a sight as three barrels in a pasture are nowadays. We’d put a bull rope on it and pretend to be riding. And with fellows jerking on each rope, the barrel could really buck. My glasses were thick, and I started wearing them at about age 6. So my rough stock fantasies were pretty much just that. I couldn’t see diddly without them. Dick Miller and I became friendly in college rodeo. He was a bareback rider and was almost as excited as I was about our rodeo team. ‘Saddle broncs,’ he told me, ‘very dangerous. All that equipment to hang you up.’ And bulls: too mean. ‘They wanna kill you.’ But barebacks: We all learned to ride bareback. He was right; at least I certainly did. ‘You just hang on.’ So at our first National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association competition in Moscow, Idaho, when Dick Miller was getting on his bareback mount, I was closely watching. I held his riggin’ as he fished under the horse’s belly with a coat hanger for the cinch. I saw how comfortable he looked when he sat down. Then he handed me his glasses and squinted at me. ‘Hold these. Okay.’ He stretched his legs forward, turned his toes out, nodded. The chute opened, and the horse sprang out 20 feet, ducked, and tossed Dick on his nose. My rough stock riding career stopped right there.”

Been Workin’

Cutting Competitions

“Nowadays cutting competitions are almost always in enclosed and covered arenas. But it wasn’t always so. One thing about the professionals: They really know how to use their equipment. And we knew it was going to get Western when they began to lose their hats. When the wind blows at the Cal Ute Feedlot in Delta, it really blows. It comes over the mountains from Nevada where it had time to build up some attitude. Delta is in the middle of a wide, flat valley, and on that day, a lot of it was blowing in the air. The feedlot seemed to rise above the valley floor at the height of 30 years of cow manure, packed and trampled into dust. It had been another summer of drought in Utah, and when the wind hits the feed lot, every living thing squints. We had arrived at the cutting the evening before, and the air was calm. But the pros started riding open horses at 9 a.m. and the wind started, too. Soon the hat rule was thrown out. Everyone was in baseball caps. The novice classes I was entered in were later in the day, so as my class began, the sun was low, and I was squinting into the wind, angling my head behind the cap bill for protection. The cattle were reruns, not a pleasant thought. The dust was thick, and I watched back-lit silhouettes of the wildly running cows. Earlier they would challenge and respect a horse, but now, fueled by the wind and experience, they just ran side to side, then closed their eyes and pushed the hapless horse back into the herd or darted under his neck and were gone. Their mood was in concert with the wind. Finally, my turn. I tried to split the herd in half as I entered, hoping to leave two Brahma sprinters on the fence, but out of the corner of my eye, I saw that didn’t work. I got some cattle out, and they started to slide back in a rush. A quick move and I had one separated, it was a terrible cut, on the run, but the cow was alone, and my hand was down. My eyes were burning, dust everywhere. I could taste the manure and dirt in my teeth. I couldn’t see my helpers or anything but the greyhound in front of me. But at least I knew the real fun had started and I could feel myself grinning.”

Different Kinds Of Cowboys

“In this century, with the range all chopped up by barbed wire, there are still plenty of people that wear cowboy hats. Our horses may live in barns, and exercise in arenas. Team ropers may have real 8-to-5 jobs. Huge trucks move cattle from summer pasture in the mountains to winter on the desert. In my travels among all those hats — the horse trainers, brand inspectors, rodeo contestants, line dancers, barrel racers, real estate developers, and dude wranglers — I have come to realize that the definition of cowboy has become pretty broad. And, surprise, somewhere over those sagebrush hills and out of sight there are still a few men and women that spend most of their waking hours working in a Wade saddle, with a 40-foot rope hanging by the horn, doing traditional cow work in all kinds of weather, for low wages. That kind of cowboy hasn’t changed much. Legendary cattleman and cutting horse trainer Buster Welch said it this way: Lots of people wear big hats, but only some are cowboys. He said: Suppose a man is riding home after a long, hard day. He’s tired and hungry. He sees a cow in a mud hole. She is really stuck, and to get her out is going to take a strong rope, a tough horse, and a lot of work. He knows that there is nobody to do it but him. And she’s not his cow. He also knows if he keeps on going, nobody will ever know that he even saw her. But if he’s a cowboy, he stops and takes his rope down, and gets to work. No question. That’s Buster’s definition. Some people use the word cowboy to describe a rogue cop in New York. But that’s not the cowboy I paint.”

Contrasting Cows

“There is an extreme contrast between cow horses that work cows day after day in mountains and meadows, over rocks and deadfall, in all kinds of weather, and horses that work cows for two and a half minutes on soft dirt as a sport. This contrast comes into focus from time to time and was especially sharp at cuttings that took place at the Meadow Vue Ranch in Idaho. The ranch was several miles off the main highway, at the edge between forest and grass. It was a beautiful setting, with the high mountains all around, and the lake down below. The annual event was held in late August or early September. Motel rooms in Henry’s Lake, the closest town, were usually filled by fishermen, and many of the cutters slept at the ranch, in their trailers or in tents. At that time of year, the mornings are downright cold, and the weather iffy. Sometimes we would awake to a little snow. I’ve always liked that cutting because it’s outdoors and pretty Western. Plenty of times we’ve stood around in the mud with our breaths showing as puffs of steam, wearing our heaviest coats over our warmest vests, sipping hot coffee, watching the rancher on a tractor dragging the arena to dry it out, hoping it will be dry enough for the precious cutters to do their thing. Our horses patiently standing in temporary panel pens, covered by the heavy blankets, some wearing hoods, quietly eating their flakes of alfalfa hay. The arena fences were all made of heavy logs, looking Western, and permanent.

Red Canyon Walls

One pen contained the contest; in the other they settled cattle. The action moved back and forth between the two pens all day. Beyond the pens was a gravel road, and beyond that, the shiny trucks and trailers with license plates from Idaho, Utah, Montana, Washington, Oregon, Arizona, and Texas are parked in a pasture. Keep looking outward, and the huge meadow spreads out, dotted with cattle, on down to the actual lake. And beyond, more beautiful forested mountains. The contrast? Between sets, when new cattle arrive, the ranch hands bring them in bunch by bunch, on horseback. Those ranch cowboys are dressed in an assortment of Gabby Hayes meets John Wayne, and ride rough horses that already have their long winter hair, dull and mud-splattered. They are bigger horses, the kind you want if you need to climb mountains day after day. As if to accentuate the contrast, the ranch cowboys whoop and yahoo if a recalcitrant cow tries an escape. A cowboy would immediately speed off to head her, pulling to a sliding stop, spraying gravel and slobber all over the West, as if to say, ‘This is how we do it out here.’”

The West Was Waiting

“Small farms lined State Road 32 in northern Utah between the Wasatch Mountains and the High Uintas. It is fertile land where grass grows and cattle and horses graze. Two small dogs welcomed me. They carried Australian sheep dog blood. They seemed plenty smart and friendly. A lady told me that Marv Thomas was up the road helping a neighbor. It was about 7 p.m. and the sun was low. The fields were turning green; in the late light the grass had a fluorescent quality. Snow-capped peaks were turning purple. The ground was pungent; nature was generous with her smells. A half-mile away, a blue pickup was parked near a smoking ditch. Three men with shovels were spreading fire further and further, burning the dead grass that choked the ditch, and stamping out the fire that wandered too far. The first man pointed me to Marvin. Marv was working late. There were lots of extra chores after the snow melted. He’d been up early. He trained cutting horses for a living, and most days he’d be horseback by 8 a.m. We talked about cutting horses. We talked as the sun set. The smell of the burning grass combined with the other smells of spring took me back to my rural youth; the conversation pulled my long dormant love of Western horses to the surface. It was getting quite dark as we finished the ditch and climbed into the pickup for a ride to the house. It had been five hours since Marvin got off his last horse, but I noticed he was still wearing his spurs. As I drove back to Park City, the sun was down and the landscape black. But there was enough reflected light on the horizon that I could make out the snow-capped ski mountains ahead of me. No lights, no town … alone with Ricky Skaggs’ music, whipping through the vast night. A quarter-century of advertising meetings had just slipped off my shoulders. The West was still here, just as I’d left it.”

Excerpted by permission. Don Weller Tracks: A Visual Memoir is available on donweller.com.

The Howell Gallery in Oklahoma City; Montgomery-Lee Fine Art in Park City, Utah; Solvang Antiques in Solvang, California; Southwest Roundup Studio Gallery in San Juan Bautista, California; Studios on the Park in Paso Robles, California; Wilcox Gallery in Jackson, Wyoming; Wild Horse Gallery in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. See Don Weller’s art July 23 – August 15 at Cheyenne Frontier Days Western Art Show & Sale in Cheyenne, Wyoming; August 7 – September 26 at Hold Your Horses! Exhibition and Sale at the Phippen Museum in Prescott, Arizona; September 17 – 18 at Buffalo Bill Art Show & Sale in Cody, Wyoming; September 17 – 18 at the Western Heritage Awards at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. With Western watercolorist Marlin Rotach, Weller is curating the exhibition The River Flows, October 2, 2021 – February 6, 2022 at the Phippen. Weller and Rotach are the subjects of the two-man show Shared Visions: The Art of Don Weller & Marlin Rotach at Northeastern Nevada Museum, December 14, 2021 – April 24, 2022 in Elko, Nevada.

From our August/September 2021 issue

Cover image: Devon and Big Z

Photography: (All images) courtesy Don Weller

Adblock test (Why?)

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.