Staying silent helped writer through COVID quarantine – The Grand Junction Daily Sentinel

[ad_1] #inform-video-player-1 .inform-embed margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 20px; #inform-video-player-2 .inform-embed margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 20px; Silent-movie star William S. Hart paid homage, not only to the Old West, but to the adventure of making movies about the Old West, when he spoke his first on-screen lines in 1939: “My friends, I love the art of making motion

[ad_1]

#inform-video-player-1 .inform-embed margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 20px;

#inform-video-player-2 .inform-embed margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 20px;

Silent-movie star William S. Hart paid homage, not only to the Old West, but to the adventure of making movies about the Old West, when he spoke his first on-screen lines in 1939:

“My friends, I love the art of making motion pictures. It is, as the breath of life to me,” he said while introducing the re-release of his 1925 classic silent Western, “Tumbleweeds.”

I love the art of early motion pictures, also. And during this enforced isolation, I’ve spent time watching silent Westerns. It’s an enthusiasm my wife and children don’t share. Nor do most readers, I suppose. But a few do.

Colorado was an early favorite for Western film-makers, especially around Golden and Cañon City. Some 50 silent-movie Westerns were made in this state, although most have been lost.

Glenwood Canyon was the location for a famous Tom Mix film. And at least one film, involving former Daily Sentinel ad man and writer Al Look, may have been filmed near Grand Junction. Little information about “Navajo Love” survives, however.

Utah’s Monument Valley didn’t become famous for movie-making until after the silent-film era, but a few silent Westerns were filmed in Utah, most notably “The Covered Wagon” in 1923.

I don’t watch silent Westerns expecting subtle plot lines. And it isn’t the nuanced acting that attracts me. Long penetrating looks at the camera and overly demonstrative physical movements are the norm.

Most of the on-screen personalities were either cowboys turned actors, or vaudeville performers who became film stars, although Hart was a Shakespearean actor prior to his movie career.

What fascinates me about the old Westerns is the production — how they filmed horse chases, gunfights, barroom brawls, cattle drives and epic events.

For instance, Hart reportedly used 1,000 people and as many horses, 300 wagons and 19 cameras for his lengthy land-rush scene in “Tumbleweeds.” The film depicts the 1889 opening of lands in what’s now Oklahoma.

One film historian said Hart’s land-rush scene still ranks “among the finest sequences of pure action in film history.”

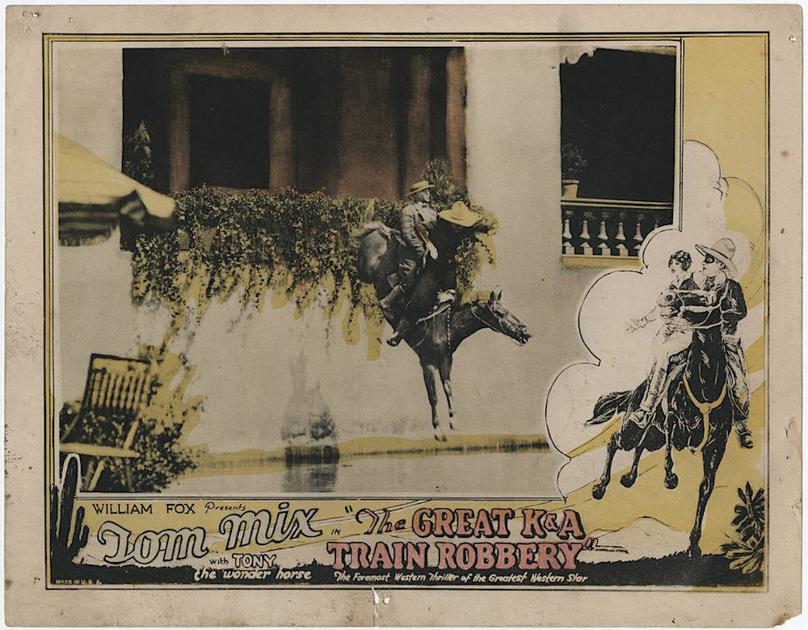

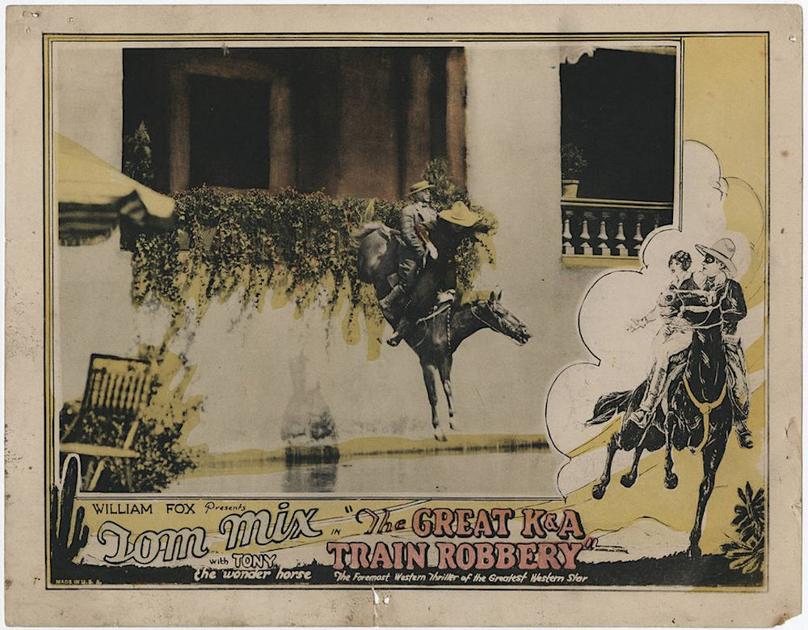

Then, there is the wonderful opening sequence of Mix’s 1925 movie, “The Great K&A Train Robbery,” filmed in Glenwood Canyon.

Mix performs what may be the first movie zip-line escape when he slides from a cliff top down a long rope and lands in the saddle on his trusty horse, Tony. Then they gallop down a dirt road along the Colorado River, snatch the damsel in distress from her broken buggy, and race safely across the narrow wooden bridge at Shoshone Dam.

Mix and fellow cowboy star Hoot Gibson, as well as swash-buckling Douglas Fairbanks and Hart, all performed their own stunts. They were experienced horsemen, athletic and not afraid of rough-and-tumble antics.

Still, injuries occurred. That’s why Hart said in 1939 that “through those feats of horsemanship that I loved so well to do for you, I received many major injuries” which helped end his film career.

Hart spent time in the West as a young man, meeting cowboys, Plains Indians and miners before he began his stage acting career. He didn’t start making movies until he was nearly 50.

He was a stickler for accurately portraying cowboys and life in the West. I appreciate that. As I view old movies, I often look to see if their costumes, horse tack and weapons are appropriate for the time- period portrayed.

Another thing that fascinates me about early films is their use of animals. Some of it was downright cruel, such as using trip wires to make horses fall.

But much of it involved great training and athletic animals.

With Mix in the saddle and another man behind him, Tony jumps out a tall window into a swimming pool, climbs out and gallops away in a scene in “The Great K&A Train Robbery.”

Hart’s horse, Fritz, jumps a wrecked covered wagon during a long gallop in “Tumbleweeds.”

I also appreciate that there was no CGI — computer generated imagery — as in the new Harrison Ford film based on Jack London’s novel “Call of the Wild.” In every other film version of the story, the dog Buck is played by a real animal, not a computer creation.

Real horses, cows, buffalo and other wild animals were used in the silent-era Westerns. Imagining how filmmakers got all those creatures to perform in concert with other animals and humans makes the films more interesting to me than CGI movies.

William Hart was the top Western movie star through the early 1920s. He was known for his serious stories and his moralistic messages. One historian said, “He made the western into a serious narrative rather than a triviality.”

Then Tom Mix, who’d been a Wild West show performer, and Hoot Gibson, a one-time rodeo champion, took over. In the Roaring Twenties, their style of easy humor, flashy outfits and superhero feats became more popular than Hart’s gritty realism.

“Tumbleweeds” was Hart’s last movie and is considered his best. After 1925, he settled down on his ranch in Los Angeles, which he donated to the city as a park and museum. It still exists.

For those who share my interest in early Westerns, here are some recommendations. A warning: Early 20th century views on race are prevalent in some of them. I found all of them through the sources listed at the end of this column.

Start at the beginning: “The Great Train Robbery,” the 1903 movie shot by Thomas Edison’s film company. Although it’s only 11 minutes long, it’s considered the first narrative Western. It was released six months before Kid Curry and his cohorts robbed a train near Parachute.

“The Return of Draw Egan,” made in 1916, is one of William Hart’s early movies. It showcases a theme Hart made famous: an outlaw who turns good.

“The Mask of Zorro,” made in 1920 and starring Douglas Fairbanks, is the first of many Zorro movies. Not a cowboy flick, but it has great stunts, sword fights and horse chases, and Fairbanks is at his athletic best.

“The Iron Horse,” 1924, was John Ford’s first epic Western. It shows his penchant for sweeping vistas, a huge cast of humans and animals and lots of action shots.

“The Great K&A Train Robbery,” 1925 is still considered one of Mix’s best films.

“Riders of the Purple Sage,” 1925. Also starring Tom Mix, this is a reasonably faithful film adaptation of Zane Grey’s most famous novel, but without Grey’s anti-Mormon bias. It has plenty of action and stunts. Prescott and Sedona, Ariz., were primary filming locations.

“Tumbleweeds” is Hart’s 1925 epic about the Oklahoma land rush. It is among the top films on lists of the best silent-era Westerns. Most online versions include Hart’s 1939 spoken introduction, which includes this heartfelt — if hokey — farewell.

“Oh, the thrill of it all,” he says. “You do give old Fritz a pat on the nose, and when your arm encircles his neck, the cloud of dust is no longer a cloud of dust, but a beautiful golden haze” through which a group of cowboys is “waiting to help drive this last great roundup into eternity.”

#inform-video-player-3 .inform-embed margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 20px;

Let’s block ads! (Why?)

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.